THE VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE OF FRANCE Christian Lassure

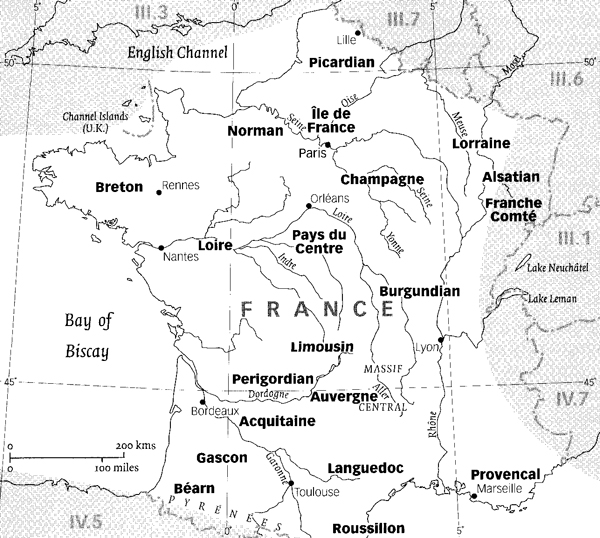

I - THE COUNTRY GEOGRAPHICAL SITUATION AND NATURAL BORDERS Situated at the western tip of Europe, France covers a surface area of 550,000 km² and has a total population of 55 million inhabitants. Since the settling of its eastern frontier at the end of the first world war, the country has never been so close to an ideal France, stretching between the seas, the mountains, and to the Rhine, just like ancient Gaul, with which it identifies itself. From its geographical situation, France derives a variety and a wealth that are unequalled in Europe. RELIEF Structurally, the country contains the three basic elements of Europe's relief : a monotonous plain in the north, a succession of low-lying ancient massifs in the centre, high Alpine and Pyrenean mountains in the south. Plains and hills, which occupy two-thirds of its territory, provide fertile agricultural lands. GEOLOGY Such varied relief results in great geological diversity. Crystalline rock (in the Armorican massif, the Massif Central, the Vosges), limestone rock (in Normandy, the Paris basin, the northern Aquitaine basin) and glacial-era deposits ensure an abundant supply of various building materials. CLIMATE Because of its narrowness between the gulf of Gascony and the gulf of the Lion (the "French isthmus"), France is at a crossroads of climatic influences: plain oceanic climate from Brittany to Flanders, continental-type climate from the Paris basin to Alsace, Mediterranean climate on the Mediterranean cornice, and mountain-type climate in Alpine regions. A wide range of agricultural crops is thus permissible. SOILS AND LANDSCAPES A country of age-old civilization, France has witnessed profound changes in its natural environment (notably its soils and landscapes) over the centuries. The climatic contrast between the Mediterranean sea and the Atlantic ocean is reflected in the typology of the soils : - red soils in the cultivated basins of the Mediterranean regions, derived from decalcified limestone; - brown soils in the oceanic regions, derived from forest soils and providing good agricultural land. Bequeathed by history, French rural landscapes fall into three major types: - the "champagnes" or areas of open fields, which predominate in northern and north-eastern France; they correspond to the old community practice of crop rotation in cereal-growing areas and to the right of grazing; they are associated with clustered housing (large villages); - the "bocages" or areas of hedged fields, typical of western and north-western France; they are an expression of agrarian individualism encroaching on communal practices; they are associated mostly with scattered housing (isolated hamlets and farms); - the Mediterranean agrarian landscape (Languedoc, Provence), in which are reflected the natural differences in relief and soil: pasture land on the "garrigues", cultivated land in the plains, orchards on the hill slopes; with this type of landscape are associated closely-built villages; Aquitaine is apart, with fields sheltered by breakwind hedges, clustered-type housing in the plains and dispersed-type housing in the hills. ECONOMIC BACKGROUND While demographically and economically the years 1800-1860 were the golden age of rural France, the following decades and the first half of the 20th century witnessed its gradual decline with the phylloxera disaster, the flight of the agricultural proletariat to the towns and the human losses of World War I. In 1931, the urban population exceeded the population of the countryside for the first time. Agriculture, which still employed over 3 million people in 1968, was employing not more than 2 million workers in 1977. The transformation of the country into a major industrial and technological power has resulted into the spreading of the French "desert" with its deserted farms and hamlets, its dwindling villages and small towns, and its houses renovated as "second homes" for city dwellers. THE COUNTRY AND ITS REGIONS The recent division of the country into 22 administrative regions, each made up by lumping together several "départements" created by the Revolution, coincides more or less with the mosaic of the major ethno-linguistic or historical provinces of the 16th-18th centuries, still alive in the minds of contemporary French people. These traditional provinces may serve as a convenient framework to describe the country's vernacular architecture. In the northern half are found Ile-de-France, Picardy, Normandy, the Loire countries (i.e. Anjou, Poitou, Saintonge, etc.), the Centre countries (i.e. Berry, Orléanais, Touraine, etc.), Champagne, Burgundy, Franche-Comté, Lorraine, plus Brittany in the west and Alsace in the east. In the southern half are found Gascony, the Basque country, Béarn, Périgord (including Quercy), Auvergne (including Limousin), Languedoc (including Roussillon), Provence, plus Savoy and Dauphiné in the south-east.

II - THE RURAL ARCHITECTURE A LAND OF ARCHITECTURAL DIVERSITY The rural vernacular architecture of France is noticeable for its great diversity, as invariably underlined in specialist studies carried out during the last hundred years. From one region to another as well as within one and the same region, a host of morphological differences can be observed in the building materials used, the pitches and volumes of roofs, the surrounds and locations of openings, the decorative features chosen, etc. However, as soon as one goes inside houses, such superficial differences vanish and one is faced with plan-forms that occur, in either uninterrupted or interrupted fashion, across regional borders or even, in some cases, national frontiers. On the scale of the entire country, house plan-forms may thus serve as a basis for the classification of farmhouses, this designation to be taken in the stricter sense of lodging unit rather than in the wider sense of residence unit (the latter comprising both human quarters and agricultural quarters). PLAN-TYPES AND CLASSIFICATION OF RURAL FARMHOUSES According to the most recent publications (P. Gaillard-Bans, C. Lassure, G. I. Meirion-Jones), the following house plan-types can be distinguished: - the single-room house, - the lengthwise house or "longère", - the upper-floor hall or "salle haute", - the house with central-corridor plan, - the depthwise house with nave and aisles. All these house-plans exist in elementary as well as derivative forms. THE SINGLE-ROOM HOUSE This used to be the house of the agricultural worker without land, implements or livestock, tied to a large estate. It consisted of a single room, closer to a square than a rectangle in plan, single-storeyed, with a hearth and oven at one of the gables. The façade, generally in a long wall, had for its openings a doorway and a small window. A table, benches, beds, a wardrobe made up the whole furniture. A single family, often a large one, dwelt there, the loft providing overspill sleeping accommodation. Although the labourer's house usually stood isolated, twin or conjoined houses or even whole terraces of houses were not an uncommon sight (as for instance in the Orléans region and Berry).

These houses sprang up in numbers during the first half of the 19th century, in response to a population boom in rural areas. As their tenants acquired small holdings, some of these houses were added a few dependent buildings (byre, wine-cellar, etc.) and turned into small farms. However, the flight from the land in the 2nd half of the 19th century was to bring about their gradual desertion, so that today they have almost totally disappeared from the countryside. THE LENGTHWISE HOUSE OR "LONGÈRE" This was the house of the small peasant (day-labourer holding a small plot, sharecropper, smallholder) and the small craftsman. It was widespread in poverty-stricken areas, and in particular throughout Western France. It is a narrow house, extending lengthwise (ie. in the direction of the roof ridge), with its openings placed more often in a long wall than in a gable wall. The strictly agricultural "longères" fall into four types according to the relationship of dependent buildings to the dwelling room: - the "longère with a single-room shared by men and animals alike, - the "longère" with a byre added to the living-room, - the "longère" with a barn-cum-byre added to the living-room, - the "longère" with a free-standing byre or barn-cum-byre, as a first step toward an open courtyard. In the "longère" with cohabitation of man and beast at opposite ends of a single room (as evidenced in lower Brittany, Normandy, Mayenne, Anjou, but also in Cantal, Lozère and the Ariège Pyrenees), the livestock was confined to the end opposite the hearth, on a sloping floor to stop the room from being submerged by liquid manure. At best, a wooden partition separated the lower-end byre from the upper-end living room. The interior layout was most rudimentary: a fireplace placed against the gable wall and prolonged by an outside oven, a sink set into the long wall next to the entrance. The furniture consisted of a table (succeeding the plate and trestles common before the 17th century), covered or curtained beds, a kneading-trough, a chest (replacing the coffer in which clothes and valuable items were put away), a dresser, a wardrobe, benches or chairs (the latter becoming common only after 1850).

THE UPPER-FLOOR HALL OR "SALLE HAUTE" This used to be the dwelling of village leaders, wealthy rural tradesmen and craftsmen (weavers, shoeing-smiths, etc.) as well as wine-growers of early Modern Times. With the advent of the industrial age in the first decades of the 19th century, it fell in the social scale and became the house of the small peasant by having a barn-and-byre added to it lengthwise. The "salle haute" consists of a ground-floor level reserved for production and storage while living accommodation is confined to the upper-floor level. Entry to the upper floor is by an external staircase and landing which are normally set against a long wall and protected by overhanging roof eaves supported by posts or pillars. While there survive only a few specimens of upper-floor halls in Northern France, the type is still extant in large numbers throughout the rest of the country, notably in wine-growing areas (higher Quercy, the Rhône and the Saône valleys, Touraine, etc.). In higher Béarn, the mountain house is of the upper-floor hall type, the ground floor serving as byre and providing access to the upper-floor dwelling via an internal staircase. The façade is in a gable wall in the older specimens, a reminder of the medieval tradition.

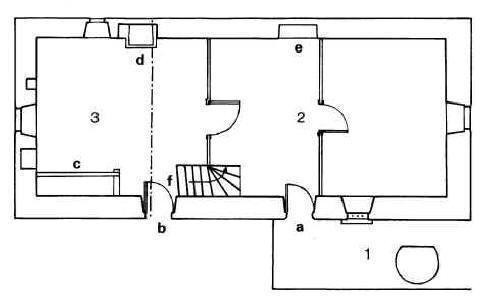

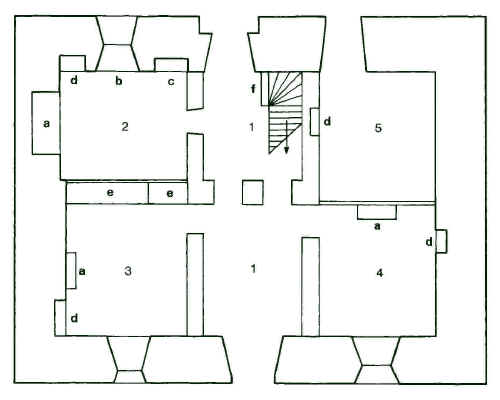

THE HOUSE WITH CENTRAL-CORRIDOR PLAN Originating in the upper classes in the Renaissance period (with the Renaissance manor-house), the house with central-corridor plan and symmetrical façade spread gradually to the lower levels of the social hierarchy, reaching first the urban and rural bourgeoisies, then the middling peasantry in the 18th and 19th centuries (as the "maison de maître"). Externally, this house presents a façade with its openings symmetrically placed round a central entrance and its elevation rising two, sometimes three, storeys high under the eaves of an imposing roof pierced by dormer windows. Internally, a central cross-passage separates two rooms at ground-floor level, one used as kitchen, the other as dining-room. The corridor contains a staircase leading to the upper floor where two bedrooms are distributed on either side of an axial corridor.

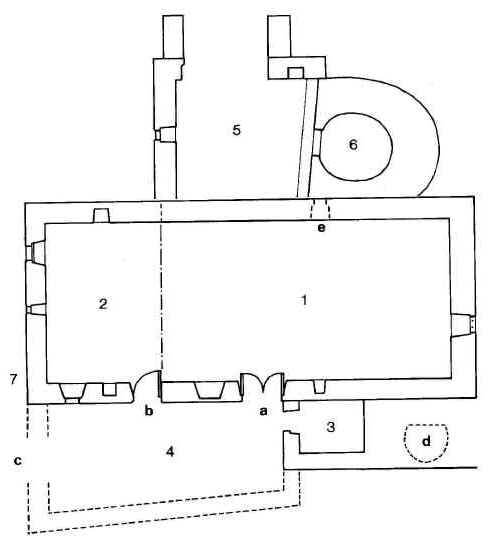

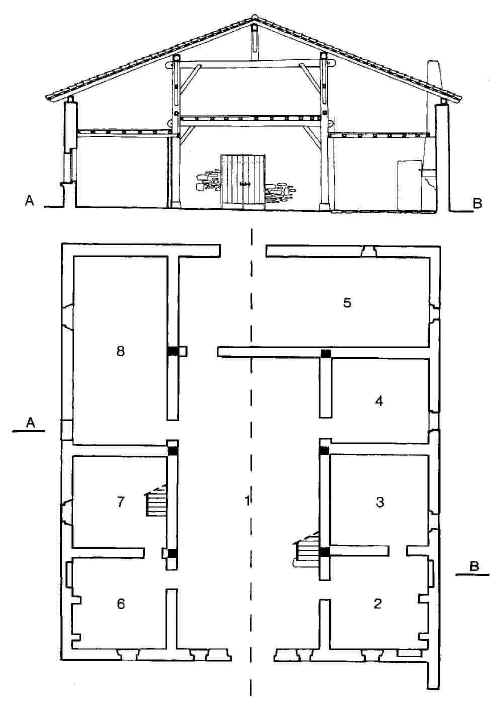

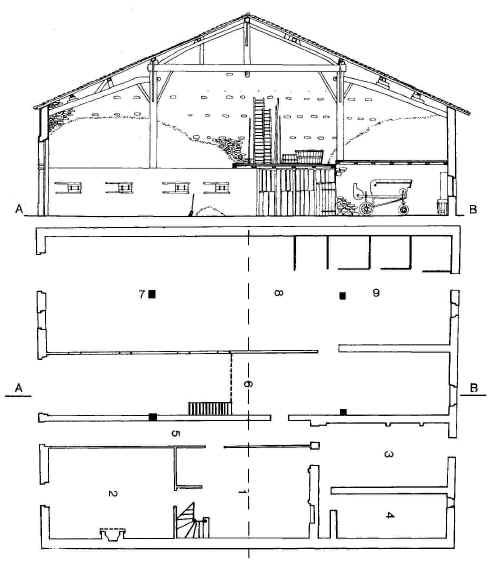

THE DEPTHWISE HOUSE WITH NAVE AND AISLES This is a house extending in depth (ie. perpendicularly to the axis of the roof ridge), with a load-bearing structure consisting of pairs of wooden posts supporting trusses, thus forming a nave flanked by two aisles or, more rarely, a single aisle. This house includes both dwelling and farming functions under the same roof, sheltering humans, cattle, implements and crops at the same time. Such promiscuity evinces a concept entirely opposed to that of the farmstead with buildings arranged round a courtyard. Houses with nave and aisles in fact were built to house agricultural tenants, first by aristocratic or ecclesiastical landlords, later by the legal or merchant middle classes. The earliest surviving specimens date back to the 17th, if not the 16th, century, the latest to the 19th. Some houses of this type were originally aisled barns belonging to large estates under the Monarchy, in which a stone lodging was subsequently installed in the 19th century. The type is encountered in relatively large numbers in the Landes, the Basque country, and in lesser numbers in the Agen region, Charente, lower Quercy, Lorraine. A few surviving examples are observable in Burgundy, Champagne, Berry, Perigord. In these houses functional division generally follows constructional division as determined by the nave- and aisle-posts. An instance of this are the surviving 17th-century Basque specimens in which lengthwise partition walls running perpendicular to the gable-façade and bridging the intervals between the posts, delimit a central nave serving as cart-shed, threshing-floor and corridor (the "eskaratza", ie. "square"), and two aisles, one containing the domestic quarters, the other the agricultural quarters, all under a large granary or hayloft. The only crosswise room is a wine-cellar or byre added to the rear of the building.

Conversely, functional division may not follow structural division, as with some specimens of the 17-18th centuries observable in the "villages-rues" of Lorraine: crosswise partitions at right angles to the original lines of posts delimit three functional bays (the "rangs"), one for the living quarters, the second for the animal quarters and the third for getting in crops, each of them possessing its own opening in the long-wall façade.

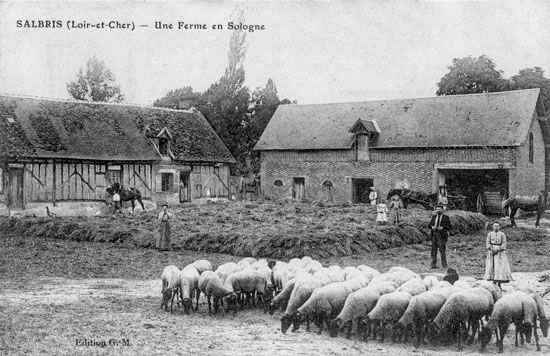

THE COURTYARDED FARMSTEAD Contrasting with the concept of the depthwise house including all the functions of a farm in one unit and under the same roof, is the concept of the farm with independent functions disseminated round a central courtyard. Within this category a distinction is traditionally made between the enclosed-courtyard farm and the open-courtyard farm. The farmstead with enclosed courtyard. It was the centre of an agricultural estate run by an owner-occupant or a tenant-farmer (the "maître") supervising a numerous staff. Even though prior to the 18th century this enclosed space may have evolved from the need to protect and defend noble or church property, later on it had for its sole rationale the necessity to offer protection against the elements or outside curiosity while remaining synonymous with economic power and social prestige. In its most typical configuration, the enclosed-courtyard farmstead consists of a yard surrounded on all four sides by buildings or walls, the only access being through a monumental-looking cart entrance combined with a pedestrian entrance. The dwelling quarters stand on the side opposite the entrance, the byres and stables occupy the sides that are perpendicular to the farmhouse, while the barn is located on the side in which the courtyard entrance is placed. The enclosed-courtyard farmstead is widespread in the cereal-growing regions North of the Loire river as far as the Belgian frontier (Beauce, the Paris basin, Champagne Pouilleuse, Picardy, Walloon Flander). Outside Northern France, it is encountered only individually or in isolated groups.

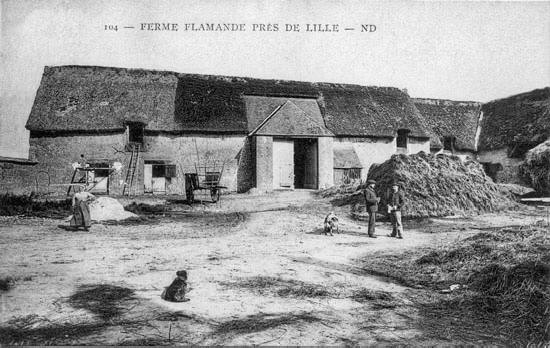

The farmstead with open courtyard. As opposed to the enclosed-courtyard farmstead, it has detached, instead of conjoined, buildings, with open intervals at the four angles. Such layout is typical of large farms where cattle-raising is a major activity: the passageways mean easy access for cattle. The type has its origin in a house such as a "longère" or an upper-floor hall growing into a farm. The distribution map of the open-courtyard farmstead extends from Western Flander to Vendée, covering all Western regions (Normandy, Brittany, Maine, Anjou); it reaches across France from Poitou to the Charolles region. Elsewhere, the type only occurs in small isolated clusters. In its extreme version, the type has evolved into the farmstead of the Pays de Caux (higher Normandy) with its edifices dotted over a grass meadow and apple orchard (the "masure") and enclosed on all four sides by an earthen embankment planted with tall trees and pierced by several gates. Or again, the farmstead of the Landes with its buildings scattered across a lawn planted with oak-trees (the "airial") and devoid of enclosures and hedges.

THE GREAT 19th-CENTURY REBUILDING Up till the mid-19th century, when a large number of rural houses and buildings were constructed or reconstructed, the prevailing materials were half-timber, puddled clay, clay cob, stones cleared from the fields, earth, etc. (for wall building), rye thatch, broom, reed, wood shingles, etc. (for roof covering), except for the houses of the wealthier classes. As a result, the architectural landscape was comparatively homogeneous across the entire countryside. By the late 19th century, this relative homogeneity had given way to a wide diversity: by acquiring property or wealth, the agricultural proletariat and the small peasantry gained access to better materials like ashlar, fired clay bricks, quarried slates, fired clay tiles, lime, etc., until then reserved for the richer classes and from then on made available to a wider public by technological progress (opening of quarries, setting up of brickworks and lime-kilns, development of railway and waterway transport). Thus, mass-produced bricks overtook Sologne during the 2nd Empire and the early 3rd Republic, being used to replace daub infill in half-timbered buildings and to erect the walls of new houses. Likewise, in higher Auvergne, coverings of thatch and stone tiles gave way, in the 19th century, to roofs of blue slate extracted from the Allassac quarries in Corrèze. This construction or reconstruction movement, initiated at a more or less early date according to the region, was first described in the "Enquête sur les conditions de l'habitation en France" (An Enquiry into the State of Dwellings in France), edited and published by Alfred de Foville and Jacques Flach in 1894 and 1899. In it are systematically contrasted "older types" and "modern types", "older farmhouses" and "newer farmhouses", namely 17th-18th century houses and their 19th-century replacements. BIBLIOGRAPHY DEMANGEON, Albert, 1946, "L'habitation rurale", chap. 8 of France économique et humaine, in Géographie Universelle (P. Vidal de la Blache and L. Gallois ed.), t. 6, La France (Paris: Armand Colin) de FOVILLE, Alfred, and FLACH, Jacques, 1894 and 1899, "Enquête sur les conditions de l'habitation en France. Les maisons-types", 2 volumes (Paris: Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques) GAILLARD-BANS, Patricia, 1979, "Aspects de l'architecture rurale en Europe occidentale", série Établissements humains et environnement socio-culturel, vol. 15 (Paris: Unesco) LASSURE, Christian, 1984, "L'architecture vernaculaire : une approche et un moyen pour la sélection des témoins architecturaux domestiques, agricoles et pré-industriels à protéger et à conserver", in L'Architecture Vernaculaire, t. 8 (Paris: CERAV) MEIRION-JONES, Gwyn I., 1985, "The Vernacular Architecture of France: an Assessment", in Vernacular Architecture, vol. 16 (VAG) © CERAV To be referenced as : Christian Lassure page d'accueil sommaire architecture vernaculaire french version

|