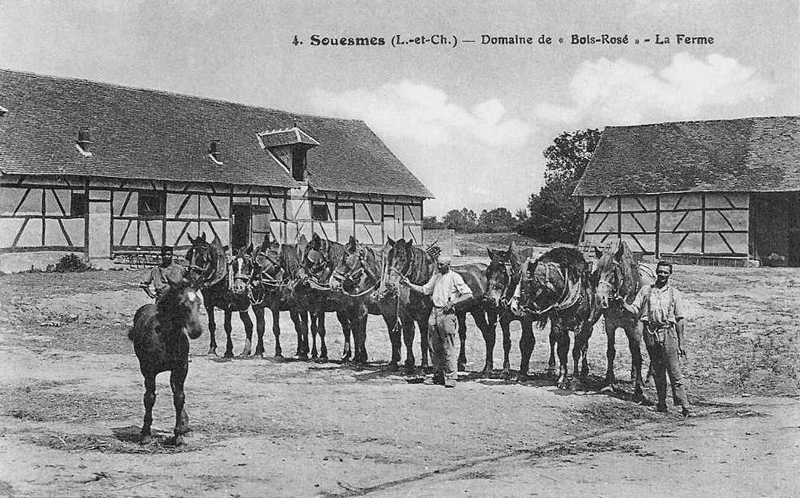

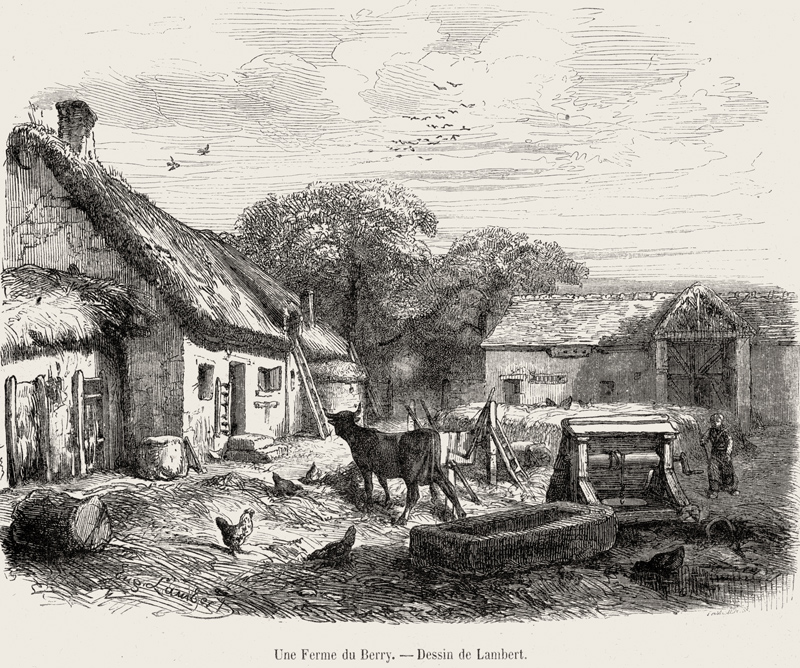

THE VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE OF THE CENTRE REGION IN THE 19th CENTURY Christian Lassure The present Centre region covers the historical territories centred on Bourges (Berry), Orléans (the Orléanais), Blois (the Blésois) and Tours (Touraine). These territories fall into twenty or so smaller areas or "pays" differentiated by geology, terrain, landscape, etc. Even though the 19th century saw the expansion of owner occupancy, the rural habitat of a large part of the Centre region bears the imprint of the form of tenure that prevailed throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, i.e. tenant farming, in which an estate (the "domaine") was let by its owner, in return for a share of the crops or fixed tithes, to a tenant farmer (the "maître") who supervised servants, farm hands and tied labourers. The estate is centred on a farmstead with a central courtyard – either open or enclosed – and a large barn, as is the case in the Orléanais, Sologne, the Beauce Chartraine, Berry, and the Brenne Tourangelle. In Sologne, two lines of buildings at right angles to the farmhouse form two sides of the "aireau" or yard, which is never totally enclosed: on one side the barn with its porch housing the threshing floor, on the other the stables or the sheep shelter. The yard is slightly sunken to allow the making of manure. In Berry, the yard is surrounded by buildings on all four sides, with, however, a narrow passageway left open at each angle, a layout harking back to a time when the yard was collectively owned by the inhabitants of a former hamlet, every house of which, except one, was subsequently turned into a dependency. In the Beauce Chartraine, the yard is completely enclosed, the only access being by a combined cart and pedestrian entrance.

In the estate, the farmhouse, invariably with a long-wall façade, may be: A functionally and architecturally important feature of the estate is the barn with, as its most outstanding ancient type, the aisled barn with a roof supported by pairs of wooden posts, a type extant in the Champagne Berrichonne and the Pays Fort. In the Orléanais, Sologne and Berry, the estate was run by employing an abundant workforce of locaturiers or tied labourers, living in nearby hamlets or villages. The locaturier's house (the locature) was a low, one-room affair, flanked at one end by a byre and at the other by a bread-oven set against the gable fireplace inside. Standing on the top of the façade wall, a “lucarne-porte” with its fixed external ladder gave access to the loft. Set into the internal wall, next to the entrance, was a rudimentary stone or brick sink – the bassie. Twin locatures or even a whole terrace of locatures, were a common sight on the outskirts of small towns.

Originating in the 17th century, the locatures were to become independent “fermettes” or small farms in the 19th century and merge into the number of small farmsteads originating from the sale of the “Biens Nationaux” (state property) and stringing together living quarters and dependencies in a single range, notably in the areas of “bocage” or enclosed land combining cattle raising and mixed farming. Apart from the domaine-locaturiers association and the "fermette", the rural habitat of the Centre region also included: Deserving special mention are the caves demeurantes or cave dwellings excavated in the tuffeau hill cliffs along the Loire river and its tributaries in the Vendôme area and Touraine. While these dwellings were inhabited by all levels of society prior to the 17th century, they were later to be gradually abandoned to the poorer sector of the population or used as agricultural dependencies.

Lastly, a word must be said of a temporary habitat linked to vine-growing and lumbering activities:

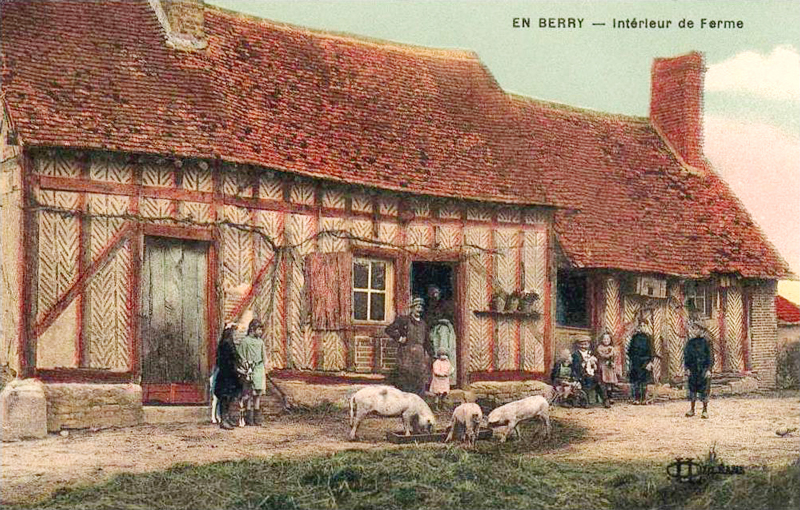

The rural habitat of the Centre region underwent, in the 19th century, a drastic rebuilding, making use of quarried stone materials or factory-produced materials. Half timber, infilled with daub, resting on a low foundation wall of flints or bricks, had been the prevailing construction material in Sologne, Puisaye, the Gâtinais and the Pays Fort until about 1840, with timber patterns of railing-like small posts or of piled-up small frames. From this date onwards, brick walling became widespread, notably in Sologne and the Perche, first as a substitute for daub infill (brickwork of headers laid flatwise or in chevron patterns), then, on reaching neighbouring areas, as the privileged material of the entire wall (losenge patterns of brown bricks). In Berry, Touraine and a large part of the Orléanais, quarried limestone became prevalent, for example as roughly coursed blocks (with or without rendering) in Beauce, Berry, the northern Gâtinais, but above all as finely cut and coursed tuffeau blocks from the Vendôme area to Touraine. On roofs, thatch and wood shingles were replaced by flat clay tiles and slates which allow the same steep pitches. Roof slates imported from Anjou along rivers or by train became prevalent, especially in Touraine and the Val de Loire.

BIBLIOGRAPHY BAILLY, Pierre, 1969, 'Notes sur l'habitat rural traditionnel dans le nord du département du Cher', in Cahiers d'archéologie et d'histoire du Berry, No 16, pp. 15-27 (Bourges: Archives Départementales) EDEINE, Bernard, 1974, La Sologne, tomes 1 et 2 (Paris-La Haye: Mouton) GAY, François, 1969, 'La maison rurale à cour ouverte du Berry', in Norois, No 63-63 bis, pp. 101-107 (Poitiers: Revue géographique de l'Ouest) SARAZIN, André, et JEANSON, D., 1976, Maisons rurales du Val de Loire : Touraine, Blésois, Orléanais, Sologne (Ivry: SERG) LASSURE, Christian, 1981, 'A propos des "maisons-halle" du Berry', in L'Architecture Vernaculaire, tome 5, pp. 33-34 et 57-58 (Paris: CERAV) ZARKA, Christian, 1982, Berry, L'Architecture rurale française, corpus des genres, des types et des variantes (Paris: Berger-Levrault) To print, use landscape mode © CERAV To be referenced as: Christian Lassure page d'accueil sommaire architecture vernaculaire

|