|

THE CLEITEAN OF THE ST. KILDA ARCHIPELAGO IN THE OUTER HEBRIDES, SCOTLAND by Christian Lassure

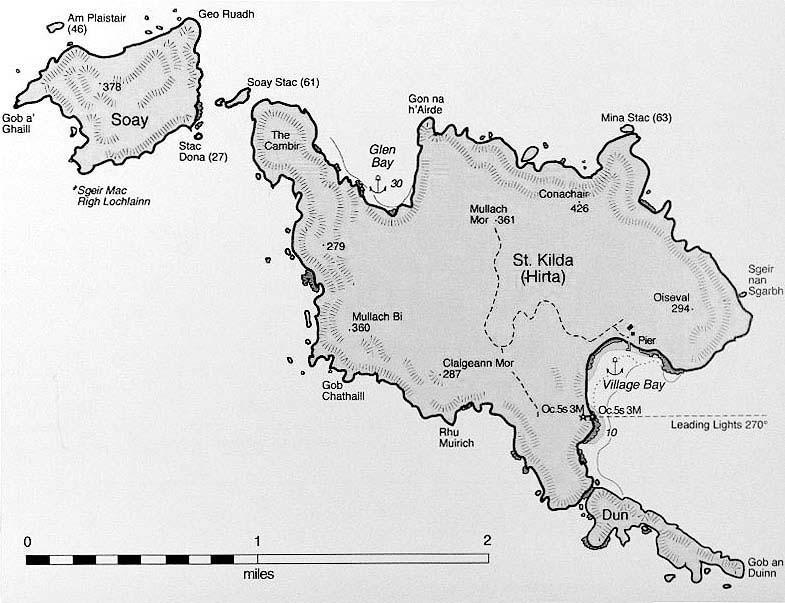

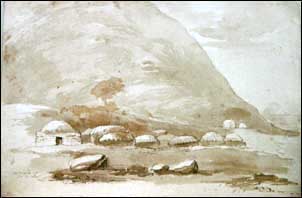

The St. Kilda archipelago lies 180 km off the North-Western coast of Scotland and 64 km West of the Outer Hebrides. It is comprised of four volcanic islands: Hirta, Dun, Soay and Boreray. The largest - Hirta - is renowned for its myriad small dry stone buildings - called cleitean (plural of cleit) in Scottish Gaelic and cleits in English - that were used as all-purpose storage huts until 1930 when the last remaining islanders left for the mainland.

The people of Hirta were crofters and sheep rearers but they lived mainly by fowling, i.e. catching seabirds and harvesting their eggs in the surrounding islands. Numbering 1300 on Hirta and 170 on the other islands, cleitean played a major role in the exploitation of the islands' various resources.

Today, the island is a national nature reserve and is included in the UNESCO World Heritage Site List. It is managed by the National Trust for Scotland and is more or less an open air museum dedicated to the enlightenment of tourists. Architectural features It is no easy task for one to try to form a precise, let alone accurate, idea of the architecture of Hirta's cleitean based simply on photographs found on the Internet. At the utmost, a number of traits shared by the majority of cleitean can be made out.

Siting Since they are sited in hilly ground - there being not many flat expanses on the island - cleitean are generally laid out in the direction of the slope with their rectilinear front end looking uphill and their rounded rear end looking downhill. In some cases however, the entrance may be placed in one of the side walls.

In one particular instance though - a hut with its apse uphill instead of downhill and not very high as a result - a small window opens in the longitudinal axis of the building.

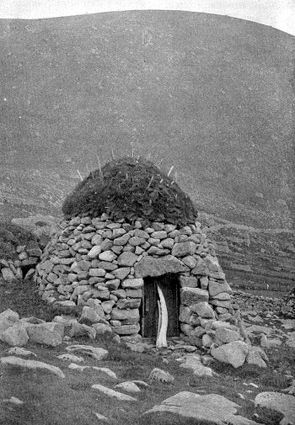

Entrance Whether it opens in a cleit's uphill end or long wall, the entrance is a low opening with sloping jambs that converge towards one another. These are made of large slabs or elongated blocks or more rarely

two large blocks set vertically (as is the case with a cleit in Gleann Mor) and are topped by a big slab by way of lintel.

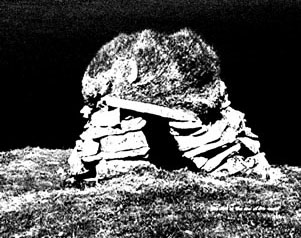

According to naturalist Richard Kearton writing in 1898, the entrance of nearly all cleitean was temporarily barred by a half dozen big stones piled one upon another; only the largest and best built huts had a wooden door to them. (*) Richard Kearton, With nature and a camera. Being the adventures and observations of a field naturalist and an animal photographer, 1898, Cassell, London. (See p. 45) Construction From a constructional point of view, cleitean consist basically of two corbelled rectilinear or convex long walls that face each other symmetrically and are separated by an interval of 0.90 m to 1.50 m at the base. These converging walls support a ceiling of large, adjoining slabs at a height of 1.20 m to 1.50 m. At one end, the two walls are joined so as to form an apse, while at the other end, their heads are joined to form the entrance's jambs.

The corbelling of the inside wall face is matched by the pronounced batter of the outside wall face.

The lack of mortar, together with the irregular shape of the stones, allows the air and wind to pass through the walls. But far from being a drawback, this characteristic has determined the basic function of the cleit as an all-purpose wind-drying store. A myriad functions (*) J. B. Mackenzie, Antiquities and old customs in St. Kilda, compiled from notes by the Rev. Neil Mackenzie, Minister of St. Kilda, 1829-43, dans Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 39, 1904, pp. 397-402 It would be interesting to find out if there is a relationship between the type of produce stored and the cleitean's siting and overall morphology. The only way to be sure of that would be to take soil samples from the huts. Whatever the answer, one must realize that, as a rule, sheep were not supposed to enter cleitean, hence the occasional wooden door or stone blocks piled up across the entrance. Although cleitean were by no means used as permanent dwellings, some of them may have provided temporary shelter to a few islanders under exceptional circumstances. It is a well-known fact that in their summer forays into the neighbouring island of Soay to collect the wool of the local sheep, St. Kildans used to take shelter in small cleitean specially built for that purpose while their expedition lasted (a week or more). It is also an established fact that the villagers had seasonal dwellings (called shielings) in Gleann Bay in the northern part of the island. As a matter of fact, the St. Kildan cleit belongs to a type of dry stone structure for air drying salted fish and meat - the skeo or skio - which was widespread in other Scottish archipelagoes like the Orkneys and Shetlands until the late 19th century. While there remain only a few rare skeos, the cleitean of St. Kilda have survived until today in considerable numbers. The Grande Dame with the wind-drying hut Legend has it that a large cleit standing amidst the village pastures was used as a lodging in the 1730s by one Lady Grange, who had been relegated to Hirta by her former husband, the Scottish Lord Advocate, who wanted her out of the way. Whoever is inclined to put faith in this fable should try to spend one night inside one of those stores in which a man cannot stand up and through which the wind whistles like the devil, as Richard Kearton found out during his visit to the island. How old are the cleitean? One should be careful not to endow the cleitean currently visible with great antiquity: Their lifespan, in Hirta's harsh environment, cannot possibly have exceeded a few centuries at most, provided of course they were properly maintained (which, by the way, is no longer the case for most of them today since the departure of the last St.Kildans). Archaeological evidence has revealed several periods of

occupation: Two incised crosses were found in reused stone blocks, the first one in a village house (could it not have been a foundation stone?), the second one in a cleit, but it really takes an act of faith to see vestiges of early christianity in them. (*) Alex Morrison, An Introduction to the Later Settlement History of St. Kilda, dans A Rock and a Hard Place; Perspectives on the Archaeology of St. Kilda, Scotland, World Archaelogical Congress 4, University of Cape Town, 10th-14th January 1999. By the 17th century the island was owned by the MacLeods of Dunvegan. One is indebted to their steward, Martin Martin, for the first detailed description of the place and the inhabitants' way of life, already centred on the catching of seabirds and the use of cleitean. He refers to three chapels built of stone and covered with thatch, but these were more likely to have been farmhouses as is suggested by the excavations being conducted at the presumed site of the chapel dedicated to Saint Brianan (Saint Brendan), at Ruaival, to the south-west of the village. (*) Martin Martin, A Late Voyage to St Kilda, London, 1698.

Hirta's golden age was the 19th century, during which the villagers' landholdings were reorganised and rationalised under the supervision of the non-resident Lord and the local clergyman while the village itself was twice reconstructed, first in 1830 with the building of blackhouses - single-roomed houses accommodating both humans and animals and having a rounded gable facing the sea), then in 1861 with the addition of 16 whitehouses - three-roomed mason-built cottages with rectilinear gables and a long-wall façade facing the bay. Any remains of the former settlement are no longer visible.

Whither the Cleitean? The archaeologists who have been entrusted by the National Trust for Scotland with the survey of the stone remains of Hirta, report in their yearly account on the damage they have seen: loosening of stones at the base of cleit 1000, crumbling wall sections in cleitean 105 and 168, collapsed angles in cleitean 120, 479 and 513, fallen lintel in cleit 799, loss of the earth covering on various cleitean, etc.). Could it be that cleitean are fragile constructions after all (incidentally just like any other dry stone building )?

One may surmise that the island's present status will warrant the safekeeping of a type of building without which the St. Kildans of old would not have been able to survive the harsh climate, isolation, scarce resources, lack of comfort, the hold the 19th clergy had over them and the yearly seigniorial levies which was their lot from the late 17th century up till the early 20th century.

This descriptive account of St. Kilda's cleitean was made easier by the outstanding photos of the built structures of the archipelago that were taken by photographer Steve Goldthorp and posted on the photo hosting and sharing site PBase.com We heartily thank Steve Goldthorp for allowing us to publish three of his photographs in this page.

Other sites or pages on the St Kilda Archipelago - www.kilda.org.uk : everything you should know about St. Kilda - www.nts.org.uk/web/site : the site of the National Trust for Scotland, in charge of the archipelago - www.flickr.com : photos of the village, houses and cleitean (in misty weather) by J. C. Campbell To print, use landscape mode © CERAV To be referenced as : Christian Lassure home page sommaire articles en anglais

|