|

VAULTING, FACING AND INFILLING

Prof. Borut Juvanec (*) Last summer I went to the region of Tomelloso, in Central Spain, to investigate about the bombos, quaint stone shelters that dot the vineyard there. They were quite an impressive sight. But above all, they enabled me to see the make-up of corbelled construction in a different light. Seeing a heap of stones, I thought it was a shelter. But it turned out to be only a stone heap. Seeing another stone heap, identical to the first one, I was surprised to find that that one was a shelter. How could that be?

In the vineyard near Tomelloso, Spain:

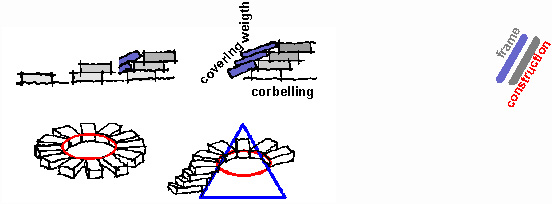

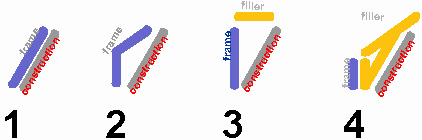

What looks like a stone heap but is in fact the rear part of a bombo The way I see corbelled construction now First point: dry stone walling (i.e. without mortar) can be found in areas where surface stone is abundant and fields have to be cleared of stones. Second point: corbelling is a constructional system in which one stone lies above another, with the position of the upper stone not exceeding its centre of gravity. This rule, however, applies only to two stones. A third stone must not exceed the centre of gravity common to all three. If the ground plan is a small circle, or if a counterweight is applied on the rear part of the stone, then the structure works. Besides playing its normal role, the counterweight can act as insulation from physical elements. While stone on house roofs normally serves as roofing material, in stone shelters all three functions (counterweight, insulation and roofing) coexist. Third point: corbelled construction involves the interplay of three components. First there is the corbelled vault proper, theoretically circular in plan. Then there is the facing or revetment, made of big stones. And finally, the infill thrown in between the two skins (corbelling and revetment) or over the roof. The infill can be waste stone from cutting, or fine stone rubble. Of course this solution is possible only in areas with little rain. Corbelled construction in theory

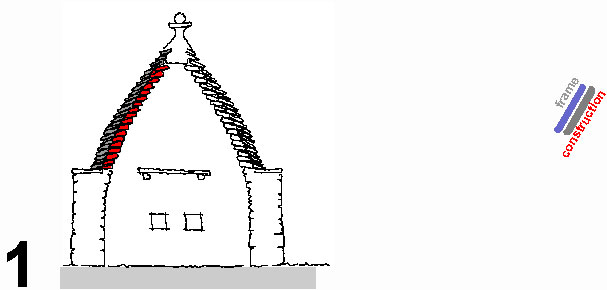

In corbelled construction two "skins" are present: the vaulting and the revetment. Although circular at the top, the corbelled vault is not necessarily so at its inception (depending on whether it is for men or for animals). The angle of the slope in corbelled vaults is 60 degrees on an average, which means that the height of a vault is equal to the square root of three by two, if the baseline is equal to one. The revetment can follow the corbelling closely, or it can be vertical in the base walls. It plays the role of outer wall as well as roofing material. Corbelled construction in real life 1 - Trullo near Alberobello, Puglia (Italy)

A trullo, near Alberobello, Puglia, Italy Corbelled vaulting and cladding joined together can be found in the roof of the trullo. The roof is constructed of flat stones inside and outside. The revetment overlays the vault itself. The roof is a double-skin affair, conformant to the theory of corbelling. 2 - Pagliaddiu at Santu Pietru, Corsica (France)

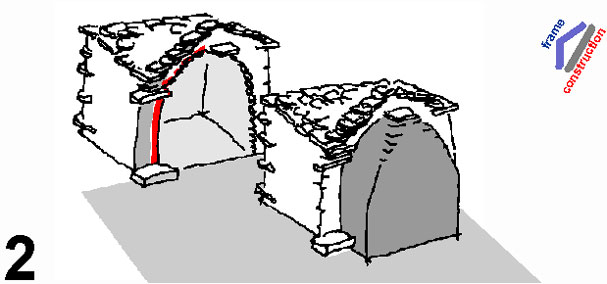

A pagliaddiu at Santu Pietru, Corsica (France) In the corsican pagliaddiu, corbelling starts at shoulder height, above the vertical wall. The revetment is vertical up to the eaves of the roof, the latter being covered with big stone slabs from the roof top down. Alternativly, the roof may be covered with earth and grass. Instead of running parallel to the corbelled vault, the revetment diverges away from it. 3 - Girna in Mistra Valley, Malta

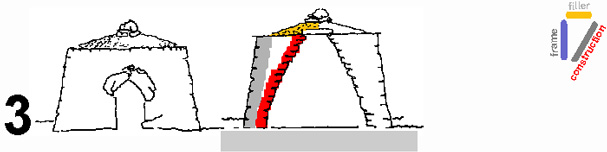

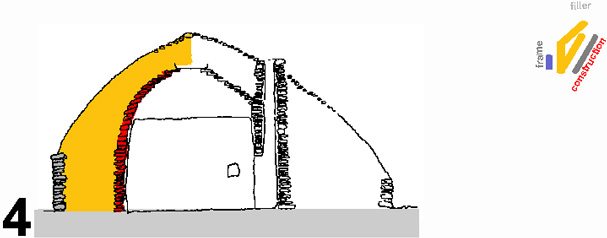

A girna in Mistra Valley, Malta The typical girna boasts a perfect corbelled vault and a nearly vertical revetment, of the height of a man reaching upwards (approx. 2.20 m). This corresponds to the height of the inner room, covered by a large slab. The roof' is made of fine stone rubble thrown over the vaulting, with a few stones piled up at the apex. Some infilling material is also to be found between the corbelling and the cladding. 4 - Bombo near Tomelloso (Central Spain)

A most interesting structure: a bombo near Tomelloso (Central Spain) In the Spanish bombo, the inner vaulting is classical corbelling (with walls plastered inside with white lime - as in living rooms - and with brown clay - as in places for livestock - as far up as a man can reach - the upper part of the corbelled vault being left unplastered). The outer revetment is simply the wall round the bombo. The infill is made of stone rubble thrown into the interval between vault and revetment. The exterior shape of the bombo follows the sliding angle of the rubble from the apex of the shelter down to the top of the wall. A bombo will have as many tops as it has rooms, and vice versa. The infill may represent ten to twenty times as much material as the vault itself. The top is sometimes adorned with a vertical stone, sometimes covered with white lime. Some bombos are still in use, as is shown by the white lime covering round their entrance or on all walls. Even the rubble may be painted white. Findings Corbelled construction involves three elements: the vaulting itself, the revetment and the infill.

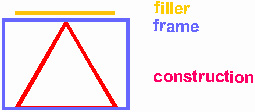

construction = vaulting, frame = facing, filler = infilling The vaulting is mostly made of cut, rough-cut or unhewn flat stones. The revetment, which also serves as counterweight, is made of big stones in the base part, and flat stones in the upper part. The infilling of waste stone or rubble occupies the space between the two, and sometimes even covers the roof. In some cases, a pile of big stones may crown the top.

Double-skin construction (together with hewn stones) is common in the trulli of Southern Italy, and in the Swiss crots (1). Where the revetment is not close to the corbelled vault, there is room for an infill of small stones or rubble, as in the pagliaddius or paillers of Corsica, France (2). The giren of Malta and some trulli in Puglia have a roof covered with stone rubble (3). The very wide wall of the bombo leaves ample space between corbelled vault and outer revetment for throwing in stone rubble. While in the first three examples the revetment defines the shape of the shelter, in the case of the bombo the appearance is that of a heap. The development cycle of stone shelters is thus ended. BIBLIOGRAPHY Egenter, Nold, Architectural Anthropology, Structura Mundi, Lausanne, 1992 Fsadni, Michael, Girna, Dominican Publication, Malta, 1992 Geist, Henri, Groupes de structures en pierre sèche, ARCHEAM, 2, Nice, 1995 Juvanec, Borut, Shelters in Stone, research, Ljubljana University, Ljubljana, 2001 Juvanec, Borut, Six Thousand Years of Corbelling, UNESCO Congress, Paris, 2001 Juvanec, Borut, Dry Stone Story, short version, Ljubljana University, Ljubljana, 2002 Juvanec, Borut, Arquitectura en Piedra Seca, Universidad Politecnica, Valencia, 2002 Lassure, Christian, Eléments pour servir à la datation des édifices en pierre sèche, ERAV, 5, CERAV, Paris, 1985 Pedrero Torres, J., Inventario de Los Bombos del término municipal de Tomelloso, Ediciones Soubriet, Tomelloso, 999 Rohlfs, G., Primitive Costruzioni a Cupola, Olschi Editori, Firenze, 1963 Tiret, André, Stabilité des coupoles en pierre sèche, ARCHEAM, 7, Nice, 2000 Zaccaria, Carlo A., ed., Architettura in Pietra a Secco, Schena Editore, Fasano, 1990 Zaragoza Catalan, A.., Arquitectura Rural Primitiva en Seca, Colleccio Politecnica, 10, Valencia, 2000

(*) Borut Juvanec, Faculté d'architecture, Université de Ljubljana, Zoisova 12 - 61000 Ljubljana, Slovénie (courriel/email: borut.juvanec[at]fac.uni-lj.si) To print, use landascape mode © CERAV To be referred to as: Borut Juvanec (Prof.) page d'accueil sommaire publications sommaire mašonnerie French version

|